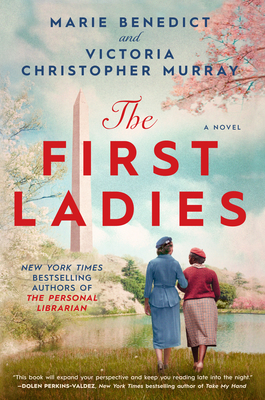

The First Ladies introduces us to two influential women of different races who become friends in 1927. Mary McLeod Bethune is an African American woman who founds Bethune Cookman College in Daytona, Florida on the site of a garbage dump. The school serves underprivileged black girls. She also finds funding for McLeod Hospital when her students are turned away by other hospitals due to their race. The book’s other main character is Eleanor Roosevelt, who by 1927 bought Todhunter School for girls and is teaching there. She also works with the Women’s Division of the New York Democratic Party to get women to vote for Democratic candidates.

Though they accomplished much by themselves, Eleanor and Mary accomplished far more together. As Eleanor’s husband Franklin Delano Roosevelt returns to public life after his polio diagnosis, Mary has Eleanor in the New York governor’s mansion and eventually in the White House to turn to when she wants more done about racism.

In the early 1930’s when FDR is still governor, Mary tells Eleanor details about lynchings that are happening in the North as well as the South. Eleanor says, “silence suggests agreement, and anyone who knows about these terrible acts—including me—should take a stand against them. Mrs. Bethune has offered me an entirely different lens through which I should be examining the racism in our country.” As a result of Mary’s friendship, Eleanor begins to take a stronger stance against racism. When FDR is elected president, Eleanor and Mary try to get his approval for an anti-lynching bill. Though FDR makes public speeches condemning lynching, they cannot get his support for the bill.

Despite some setbacks, Mary and Eleanor brainstorm ways to help blacks during the Great Depression. Eleanor asks, “How shall we begin to ensure that the New Deal is indeed for everyone?” They plan to get black people into administrative positions in the government as well as finding them jobs. For example, Eleanor recommends Mary to a position with the National Youth Administration. After Mary speaks to FDR about the importance of funding for black youth, he decides to create a division within the NYA to focus on the needs of blacks and puts Mary in charge. In three months, Mary doubles the funding for NYA’s Division of Negro Affairs.

Just as Mary changes Eleanor’s opinions on racial issues, her friendship with Eleanor changes how Mary votes. She voted against FDR when he first ran for president, but she votes for his second term because blacks are now included in New Deal programs.

During FDR’s second term, Mary makes a persuasive speech to him about including blacks in pilot and combat training and adding more black army units. Mary and her male allies in the black community also get FDR’s promise to issue an executive order ending discrimination in the military. Yet the bill languishes on the president’s desk for so long that the black community threatens to stage a mass protest in Washington, D.C. Fortunately, Eleanor convinces him to sign the bill, preventing the protest.

I always feel that the main job of historical fiction is to make readers interested in learning more about the topics in it. The First Ladies succeeded in making me want to find out more about Mary McLeod Bethune, who I knew almost nothing about before. The dual points of view of Mary and Eleanor worked well, though I could’ve done without some of the details of Eleanor’s childhood. To be fair, I know more about Eleanor Roosevelt from reading biographies about her, so less familiar readers may not mind the extra information.

My main criticism of the book is that it put Mary and Eleanor together in important historical situations when they were in different places. For example, Eleanor visits the Tuskegee Institute’s airfield to make a point about how safe it is to fly with an African American pilot. The book includes Mary on this trip even though she wasn’t there. Fortunately, incidents like this are rare in the book (it only happens twice). I realize the book is historical fiction but feel it’s important to maintain historical accuracy whenever possible.

This is the second historical fiction book I’ve read recently that explores the power of female friendships, and in this case, what female friends can accomplish together. I enjoyed the focus on friendship rather than a romantic relationship. The First Ladies shows Eleanor and Mary as true friends, despite the racism of the time. As Victoria Christopher Murray wrote in her author’s note, “at the core of any relationship is trust, and Eleanor and Mary had that. They trusted each other and felt free to share, to laugh, to cry…and sometimes even get annoyed with each other.” I recommend The First Ladies to anyone looking to explore the wonderful friendship between an influential black woman and an influential white one.