Early marriage was encouraged in ancient Egypt. A suitable age for men was 20 but the bride would be younger, probably around 14 years old. There were no legal age restrictions on marriage so younger girls married too.

Ancient Egyptians usually married within the same social class. Marriages between cousins or an uncle and a niece were desirable because it would prevent splitting up family property. Though marriage between brothers and sisters happened within royal families, it wasn’t a widespread practice. Unfortunately the ancient Egyptian habit of using the words “brother” or “sister” as terms of affection made it seem that many more brother/sister marriages took place. Polygamy was also uncommon since a man needed to be rich to provide for many wives.

Marriages were agreed to by the father of the bride and the groom. Unlike modern weddings in western societies, there was no ceremony or exchanging of rings. The ancient Egyptians didn’t even have a word for “wedding.” The bride simply moved her possessions to her new husband’s home. Nevertheless, the ancient Egyptians loved parties so wedding banquets were likely.

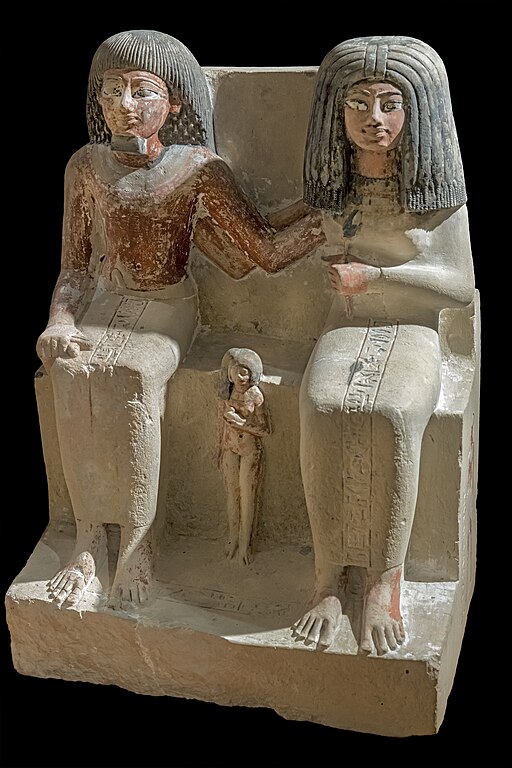

The unceremonious nature of Egyptian marriage didn’t mean that couples felt no affection for each other. Indeed, the sheer volume of Egyptian love poetry indicates the opposite. One such poem begins: “My love is one and only, without peer, lovely above all Egypt’s lovely girls./On the horizon of my seeing, see her, rising,/Glistening goddess of the sunrise star bright in the forehead of a lucky year.” Ancient Egyptian statues and tomb portraits also portray husbands and wives sitting side by side. The husband’s arm might be around his wife’s shoulders or vice versa. Though the poses may not seem romantic to modern eyes, few other ancient civilizations showed that much affection between married couples.

Ancient Egyptian wives also had certain rights that other ancient married women did not. The wife was allowed to own property, and to have a share of any property acquired during the marriage. Ancient wisdom texts show the respect due to a wife. The Instructions of Ani exhort young men: “Do not control your wife in her house when you know she is efficient. Do not say to her ‘Where is it? Get it!’, when she has put it in the right place. Let your eye observe in silence. Then you recognize her skill.”

Wives, like husbands, could also initiate a divorce. Marriages dissolved in much the same way as they began. The wife usually returned to her family home, taking her possessions and her share of the property. Sometimes she received some financial support from her former husband. Marriages ended for various reasons. Sometimes the couple was incompatible, sometimes one party fell in love with someone else, or the wife was infertile and the husband wanted children. Having an infertile wife was not considered an appropriate reason for divorce, but it happened anyway.

Infertility was invariably blamed on women. The main point of ancient Egyptian marriage was to have children, especially sons who could continue the family name and make sure the proper rituals were performed for the parents after death. Wives needed many children to please their husbands, ensure security in marriage and to enhance their social status.

Yet children were not merely status symbols. Tomb scenes show affection of parents to both boys and girls. Though boys were preferred, there was no established tradition of female infanticide in ancient Egypt.

Marriages in ancient Egypt could also end through death. Young girls who married uncles were often widowed and women could die in childbirth. Tomb scenes show loving couples being reunited after death. Remarriage after widowhood was also common, with some ancient Egyptians remarrying multiple times.

Sources:

Ancient Egyptian Literature: An Anthology Translated by John L. Foster

Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt by Joyce Tyldesley

Egyptian Life by Miriam Stead

Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt by Jon Manchip White